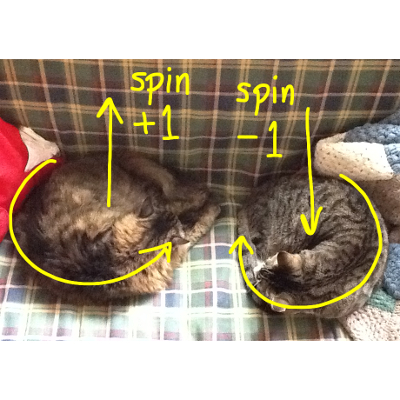

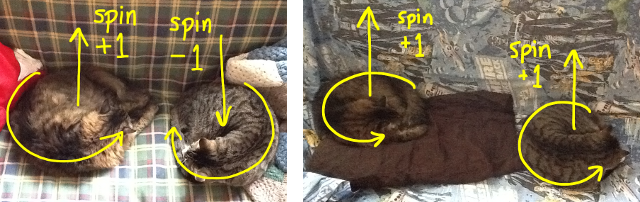

A few weeks ago, I wrote an article for Fermilab Today about the spin of fundamental particles and the Higgs boson in particular. My cats were eager to demonstrate how photons emerge from a Higgs decay in an anticorrelated state, so I included them as Figure 1. It was wildly popular. I was even asked to present it as a talk, which gave me a chance to expand on the topics that I had raced through to stay within my 800 word budget.

Spin is interesting for a lot of reasons. At the moment, it is perhaps the most important unknown parameter of the new particle discovered last July. Spin is also at the heart of quantum weirdness, because it’s an “amount of rotation” that is somehow quantized like a light switch: on or off, and never in between. It seems like we could just put a particle on a slow enough turntable to dial up a non-quantized angular momentum, but nature has a way of enforcing its rules. Talking about spin also makes for a nice bridge between the world of subatomic particles and the world of everyday experience, since it has some macroscopic consequences.

I don’t harbor the illusion that the popularity of my article was due to anything but Cats On The Internet, however.

Angular momentum

In the original Karate Kid movie, the kid who wants to learn karate is frustrated by his teacher’s insistence that he spend his time painting fences and waxing cars. Only later is it revealed that the student had learned the fundamental moves without realizing it, blocking punches with “wax on, wax off.” In much the same way, the deepest mysteries of physics are taught in Physics 101, but they’re hard to recognize in everyday objects like bicycle wheels and spinning tops.

One of these deep principles is the conservation of angular momentum. Angular momentum is the amount of rotation an object has, taking into account its mass and size, and it is curiously constant. A spinning figure skater has a constant angular momentum as she contracts her arms and twirls faster because a fast-spinning small object as as much angular momentum as a slow-spinnging large object. A cloud of interstellar dust, stately drifting in a slow inward spiral, can eventually collapse into a pulsar the size of a city block, feverishly revolving around its axis a thousand times per second. The angular momentum stays the same.

Fundamental particles are, as far as we know, infinitesimal points of zero size. If a figure skater or a dust cloud could shrink down to a single point, would they rotate infinitely fast? Is it even meaningful to say that an object rotates when it doesn’t have any extension in space? Whether the particles are actually moving or not, they have angular momentum and conserve it just as a macroscopic object would. The fact that they have angular momentum and maybe not motion suggests that angular momentum is the more foundational concept.

Another odd thing about the angular momentum of individual particles is that it is quantized. An electron always has an angular momentum of , either in its direction of travel (

) or opposite to it (

). A photon always has

. This constant,

= 5.27×10-35 Joule-seconds, is also the minimum uncertainty in Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle:

which means that the uncertainty in a particle’s position () times the uncertainty in its momentum (

) is always at least

. There’s a deep relationship between this uncertainty and the quantization of angular momentum, which can be explained in terms of phase space.

Phase space

Phase space is another workaday tool in classical physics that turns out to have deep implications in quantum mechanics. It is simply a plot of momentum (velocity times mass) versus position. If we’re only interested in one spatial dimension, then phase space is two-dimensional. If we’re interested in three spatial dimensions, then phase space is six-dimensional, since there’s a component of momentum for each component of position. Phase space is not another world, just a way of representing problems.

To give a sense of how phase space works, I’ve put together a demo that plots momentum versus position for a simulated pendulum that you can move with your mouse. It requires a plug-in from Unity (a video game engine) that installs fairly easily on non-Linux laptops. (Unity is wonderful: you just set up physical objects and let it simulate all of their complex interactions. I’ve been having fun.)

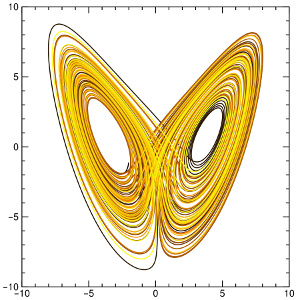

Phase space of a chaotic system known as a Lorenz attractor.

As you can see in the demo, the pendulum occupies a single point in phase space at a given time, and that point is always moving. In the center of its swing, the position is near zero but its momentum is large. At the turn-around points, the position is far from zero but the momentum is passing through zero. A nice, smooth swing traces an ellipse in phase space, but if you grab the ball and bounce it, you get more complex patterns.

If a system has an unpredictable or even fractal phase space pattern, it is called “chaotic.” Although chaotic systems are classical, with no quantum uncertainty, their outcomes cannot be predicted because they are hypersensitive to the initial position and momentum of the system. No position or momentum can be specified with infinite precision, just arbitrarily high precision (in classical physics).

My pendulum demo is not chaotic: if you let go of the ball in a slightly different place, it might bounce a bit more at first, but it eventually settles into a regular orbit. A chaotic Lorenz attractor (see figure), orbits one point for a while, then switches unpredictably to another, and back again. Some unstable systems start in a smooth orbit but eventually fly away with no fixed points.

This chaotic/non-chaotic dichotomy is a mathematical abstraction. At a very small scale, phase space is granular, which moots the question of sensitivity to arbitrarily small regions of phase space. A real, quantum mechanical system never occupies a single point on the plane, but a region with area equal to . (The units of

, Joule-seconds, are the same as meter-Newton-seconds, which is length times momentum.)

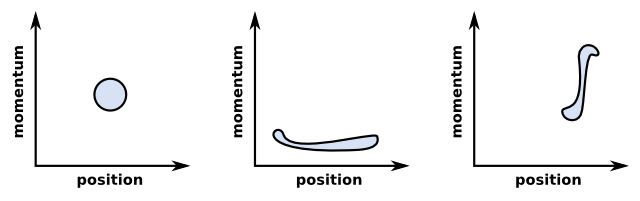

Regions of phase space with equal area: the shape does not need to be the same to be quantized.

One way to think about this extension in phase space is to call it uncertainty. We imagine that the true position and momentum are somewhere in the blob, and we don’t know where. If the momentum is very precise (middle figure), then the position must be uncertain; if the position is very precise (right figure), then the momentum must be uncertain. That is the meaning of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, .

However, many experiments in quantum mechanics force us to say that the system is occupying all points within the blob simultaneously. I prefer to think of the system as actually spreading out over that area.

Quantized angular momentum

The formal definition of angular momentum () is position (

) times momentum (

):

,

which means that angular momentum can be represented as an area in phase space. It must therefore be quantized in units of . The same effect that blurs the positions of particles makes their angular momentum rigidly discrete.

Each type of particle has an intrinsic angular momentum, called spin. For brevity, spin is called spin-1/2,

is called spin-1, etc. All known fundamental particles fall into two categories: spin-1/2 and spin-1. Higgs bosons and gravitons, both strongly believed to exist, add another two categories: spin-0 and spin-2.

| spin-0 | spin-1/2 | spin-1 | spin-2 |

| Higgs bosons | Quarks, electrons, muons, taus, neutrinos | Photons, W, Z bosons, gluons | Gravitons |

Particles bound in combinations, such as the three quarks in a proton, have additional angular momentum from the particles orbiting each other. This, too, is quantized. In fact, if any angular momentum in the universe were not quantized, then all of it would not be quantized, since we would be able to transfer the fractional part from one system to another.

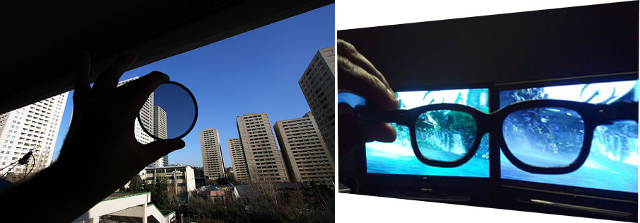

The spin of photons, particles of light, is known to photographers as circular polarization. A photon’s spin can point in the same direction as its motion (“spin +1”) or opposite to its motion (“spin −1”), and these are the “right-handed” and “left-handed” polarizations.

Left: polarized camera filter. Right: 3-D glasses: each lens filters a different polarization, so that the two eyes see different images. It’s a fortunate accident of biology that humans have as many eyes as photons have spin states.

My objection and Nature’s rebuttal

It seems ludicrous for something like rotation to be quantized. If a particle has spin-1/2, why couldn’t we just put it on a record player and rotate it the other way, at a rate less than ? Angular momentum isn’t exactly the rate of rotation, but it’s close enough that this seems like a paradox.

Physics is an experimental science, so we can just try it and see what happens. When you try to spin down a single particle or look at its spin from different angles, it occupies both the spin-up state and the spin-down state with different probabilities. To make any conclusion, one must measure event rates with an ensemble of particles, and that doesn’t completely answer my appeal to common sense.

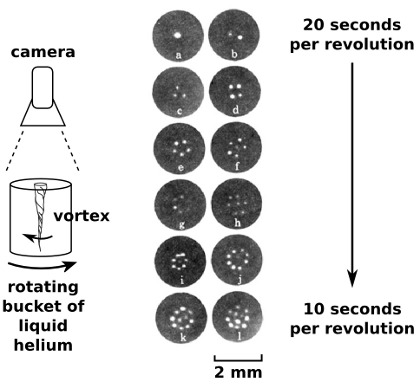

Some quantum systems are big enough to see by eye, such as a bucket of liquid helium, and this makes quantum mechanics almost tangible. When cold enough, the whole body of liquid acts as one giant quantum state with quantized angular momentum. On a turntable, it resists attempts to rotate it by forming vortices that spin the other way. The vortices are quantized, and they add up to the appropriate angular momentum by arranging themselves in a triangular grid.

Nature finds a way.

Pictures of quantized vortices in a superfluid, photographed from above. (Yarmchuk, Gordon, and Packard, Observation of Stationary Vortex Arrays in Rotating Superfluid Helium, 1979).

Spin of the newly discovered particle

Only a few facts are known about the particle discovered this July: it decays to

When a particle decays, conservation of angular momentum requires the spin of all the decay products to add up to the spin of the original particle. The decay products can even emerge from the decay orbiting each other, which adds to the total angular momentum. Nevertheless, some decays are impossible due to angular momentum mismatches, and we can use this fact to deduce the spin of the original particle.

Of the decay modes listed above, the most restrictive is the decay to two photons. Photons are spin-1 and massless; the only ways to satisfy the accounting are:

(spin 0) = (spin +1) + (spin −1)

(spin +2) = (spin +1) + (spin +1) or

(spin −2) = (spin −1) + (spin −1) or

The photons are either spinning in opposite ways (original particle was spin-0) or the same way (original particle was spin-2).

It took hours to train them.

Unfortunately, we can’t use something like a polarization filter to measure the spin of these photons: they’re 30 billion times more energetic than visible light and register in the detector as a shower of high-energy particles, rather than a well-behaved wave.

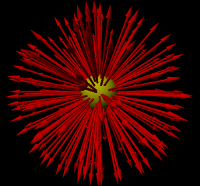

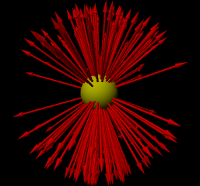

Instead, we use the fact that spin affects the pattern of particle decays. When a heavy particle decays into two light particles, the angle of the decay products is random, but there is a trend in the randomness. With enough events, we can see if the decays match one pattern better than the others. We do not yet have enough events to tell whether the newly discovered particle is a spin-0 Higgs boson or a spin-2 graviton, but the datasets are growing.

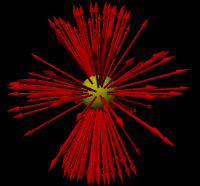

| spin-0 | spin-1 | spin-2 |  |  |  |

Spin-0 decays in all directions with equal probability; spin-1 prefers decaying toward or away from the direction of spin; and spin-2 prefers the poles and the equator to the region in between. These pictures exaggerate the real distributions for clarity.

This is the main reason that physicists are cautious about calling it a Higgs boson. If it’s not spin-0, then it can’t solve the problem that the Higgs mechanism was invented for. It would be some new, unexpected particle— certainly welcome, but not the Higgs.